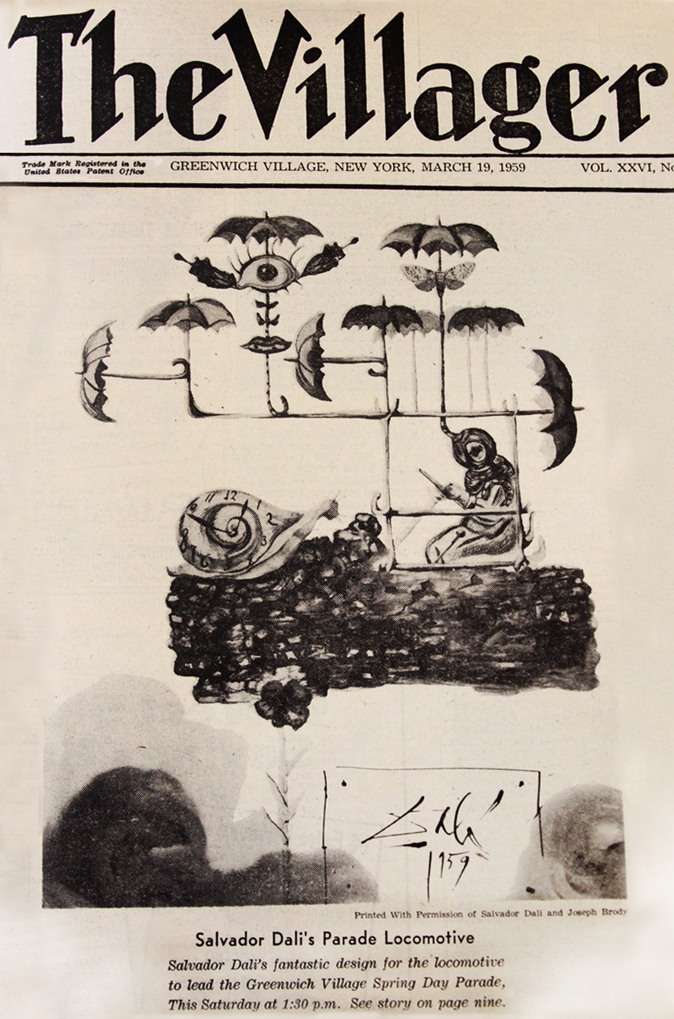

"Loconik": Conveyance designed by Salvador Dali'

One of Brody’s more unusual ploys to bring in customers was a free tour of Greenwich Village, a service he began offering in March 1959. The tour was conducted first on a “train” and then a “bus,” both designed for the purpose by Salvador Dalí. Each was called the “Loconik.”

The Loconik first appeared on Saturday afternoon, March 21st, 1959, at 1:30 p.m., leading the Greenwich Village Spring Day Parade – its appearance there sponsored by Joseph Brody.

From The Villager, March 19, 1959

William H. Honan of The Villager, a co-sponsor of the parade, interviewed Dalí, in his room at the St. Regis Hotel, on the Loconik, in advance of its appearance:

Salvador Dalí’s two-pronged waxed moustache was immediately recognizable. He is a short, rather stocky man with long, black hair…. [Dalí’s] room was cluttered. On the left, as we entered, there was a tray of oil tubes and an easel supporting a fresh canvas on which several delicate blue and yellow butterflies had been painted. To the right: a desk piled with photographs, and a small table jammed with, among other things, a huge snail shell with a light inside…. We sat down in a circle….

“We’re delighted with your contribution to the parade,” I started, “but we’re not quite clear about its exact meaning or purpose.”

Dalí’s face lit up. I couldn’t have said anything more flattering.

“Confusion! Dalí creates confusion!” he exclaimed. “And if you’re not any clearer after we talk, call me tomorrow and I’ll offer you more obscurity.”

Accepting him at his word, I asked if he would kindly confuse me about the umbrellas on his locomotive.

“Dalí all the time creates the contrary of everything,” he said. “The umbrellas mean pleasure…. The umbrella is the skeleton on the outside,” he said, “like a lobster…and the umbrellas should have water coming out of them, instead of falling on them.”

Mr. Mardus [the parade coordinator] interrupted here to note the great cost of creating umbrellas that would rain themselves instead of just conventionally resist rain. Couldn’t Dalí use soap bubbles instead?, he suggested.

“Soap boobles?” repeated the master. “Yes, Dalí is also a diplomat. We shall have soap boobles. Inside Dalí’s locomotive, it is snowing!” But he warned us that if the locomotive were not built according to this design in all other respects, he would not ride on it during the parade.

Mr. Mardus explained that a crew of men were working night and day to build the locomotive on schedule for the parade this Saturday. “The more the builders suffer,” Dalí replied, “the better Dalí’s locomotive will be. It is not easy to build this rhythm of confusion which is poetry….”

The more we scratched our heads, the more enthusiastic Dalí became. He told us that the chassis of the locomotive was to be made of real coal because coal is “man’s subconscious” and also the “source of all energy.” He had wanted to build the locomotive ten stories high. He had wanted it to “breathe” like an animal. Any nation that can send a rocket into space, he said, can certainly build his locomotive…..

I realized I hadn’t asked about the great eye or the lips on the locomotive…. He listened to my question about the eyes and lips, paused a moment, and said, “Dalí’s locomotive has sex appeal!”

….We reported [to Brody] on the conversation with Dalí. “The man is fabulous, really fabulous,” said Brody. Incidently, “what are you spending on all this? I asked. Brody smiled painfully. “Back in September,” he said, “when I conceived of the idea, I planned to spend $4,000. Now Dalí’s locomotive will cost $16,000…. But Dalí is charging me nothing,” Brody added. “He’s doing it for the community. He loves The Village. So do I. I’ve made my fortune there. I want to give something back to the people.”

The original “Loconik,” at a “Save The Village” demonstration at city Hall New York Times, February 18, 1960, p. 25.

Once the parade was over, Brody began using it for his free tours of the Village for patrons of his restaurant – featuring it in his ads.

In October 1960, Brody retired the original Loconik in order to replace it with a larger version, also designed by Dalí. From a catalog for a Dalí exhibition called Dalí: Mass Culture:

October: He designs a bus for Joe Brody of the Albert French restaurant, which is extended to enable it to take 15 more passengers on its route through Greenwich Village. The original is donated to the zoo in the Bronx, where it is stored in a garage.

As described in The Villager:

High noon tomorrow marks the final journey for Salvador Dalí’s “Loconick” [sic].This hourly sight-seeing vehicle will make its last run from Albert’s French Restaurant, 40 E. 11th St. – to be replaced by a larger vehicle.

This unique three-car rubber-tired “train” which has a top speed of seven miles per hour was designed by Mr. Dalí and built at a cost of $25,000 at the request of Joe Brody, a Village enthusiast, who operated and ran the tour free of charge to anyone visiting the Village.

A larger, more efficient and streamlined vehicle will take over the free tours as the Loconik leaves. Shaped like a huge chunk of coal with a two-foot eye and a score of umbrellas atop, and two snails alongside, the device has been accepted by New York City as a gift for children visiting the Bronx Zoo.

The Bronx Zoo, however, apparently didn’t highly value the Dalí design:

A vehicle designed by Salvador Dalí to resemble a ton of coal was donated yesterday, not to a museum, but to the Bronx Zoo, where it will be kept in a garage, not a cage.

The vehicle, an industrial tractor in deep disguise, has been used for more than a year to pull a two-car sightseeing train through the streets of Greenwich Village – a service provided without charge by Joseph Brody, a restaurateur.

Zoo officials received the gift with a nice blend of vehicular gratitude and esthetic distaste.

Standing in front of Mr. Brody’s restaurant at 42 East Eleventh Street, Gordon Cuyler said: “We’ll have to paint it. I can’t guarantee to keep the Salvador Dalí design. We have a sign painter at the zoo, and it may be that he’ll put some insignia on the side.”

At the zoo, Charles Driscoll, superintendent of operations, said the surrealist coveyance [sic] would go into the shop for the winter, where it would be made to conform to the zoo’s fleet of former World’s Fair tour trains.

Beginning next April, it will haul zoo visitors from the Boston Road entrance to the fountain circle.

In a fourteen-mile ride from Greenwich Village to the zoo, the little train showed a remarkable sensitivity to wrinkles in the roadbed. Having no springs, it registered manhole covers with teeth-rattling fidelity. Even at the mad pace of twelve miles an hour, Mr. Brody repeatedly shouted out appeals to the driver to have a care.

He explained that the functions heretofore performed by the train would henceforth be fulfilled by a bright red school bus that pulled up at his door before the trip to the zoo began. Rides in the bus will also be free.

Asked if it was true that he was a “wealthy and legendary eccentric,” as an aide

had described him, Mr. Brody said, “I’m not wealthy, but I’m crazy.”